by Vicky Masson

‘Why do we teach…?‘ is a column of Language Teaching Lab. It might help us think deeper on why we teach a certain topic. In addition, it might show a new perspective on how to teach it.

This was me back then

How do you teach to describe people? For a long time, early in my career, I embraced the typical unit on how to describe people wholeheartedly. Most of all, I loved teaching descriptive words. In particular, I was so happy to teach my students how to say the eye color in Spanish.

What a great way to show that ‘green eyes’ or ‘brown eyes’ would become ‘los ojos verdes’ or ‘los ojos marrones’ in Spanish.

I would emphasize the sentence structure needed in Spanish compared to English:

- articles + nouns + colors/adjectives – in Spanish

- color + noun – in English

Moreover, I was delighted to explain how to use the articles and the colors in the plural form, a concept that was extremely difficult to grasp for my learners. To make things even more complicated, I happily added that in the case of ‘brown eyes’ you could also say ‘los ojos café’ where the adjective remains singular!

My students would practice saying the eye-color through describing family pictures, friends and playing ‘Guess Who?’

I used to teach article-noun-adjective-verb agreement through this unit and I felt accomplished. I was teaching about the language and not necessarily to think and communicate in the language.

Fastforward, I don’t do that anymore

So, what happened? Teaching evolves. Language research provides new approaches and methodologies. We study. We read. Suddenly, it doesn’t make any sense to describe people for the sake of teaching agreement. I mean, I continue to explain the importance of agreement in class to avoid comprehension gaps, but I explain it depending on the functions we use and of course, always in context.

One aspect of teaching that has changed is the push for the decolonization of the curriculum. We want to be inclusive in our teaching. We want to consider the variety of voices that encompass a language. And in doing so, we fall into another trap.

We often present our learners with a textbook unit, where they showcase people from another culture that are probably different from our students, and we ask students to describe them. Without realizing we may perpetuate stereotypes by doing so. We are pointing out differences in our humanity without celebrating them.

How do we break this cycle?

One way I broke this cycle of perpetuating stereotypes in my classes was by referring to the cultural iceberg to frame my teaching.

Students define culture, iceberg, and talk about what the phrase cultural iceberg may mean in their own words.

After we brainstorm what a cultural iceberg could be and what it could be about, we describe visuals, read articles, and watch videos about the cultural iceberg. Even novice learners can do this. It is a question of finding the correct resources, scaffolding the teaching, and putting students into the driver’s seat.

Then, I ask students what words come to mind when they ‘describe people.’ We brainstorm ideas on physical characteristics and personality traits that they could use.

A task that has proven effective for perspective taking was to ask students to describe themselves by their personality traits first. Then, to compare themselves to a family member. Most importantly, have them think about what personality traits from their chosen family member they would like to have themselves and why. This challenged them to put themselves on someone else’s shoes.

After connecting the cultural iceberg to describing people, I asked why it might be important to be able to describe people in Spanish. We talked about people as prisms, gems, and multifaceted unique beings.

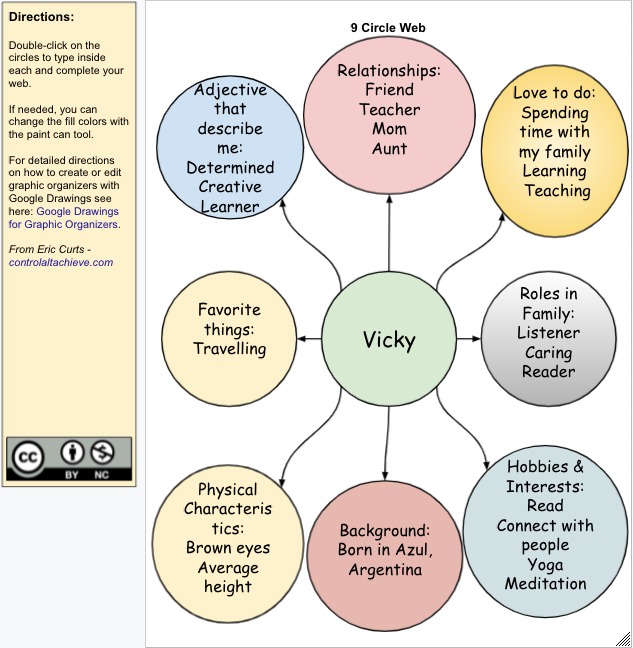

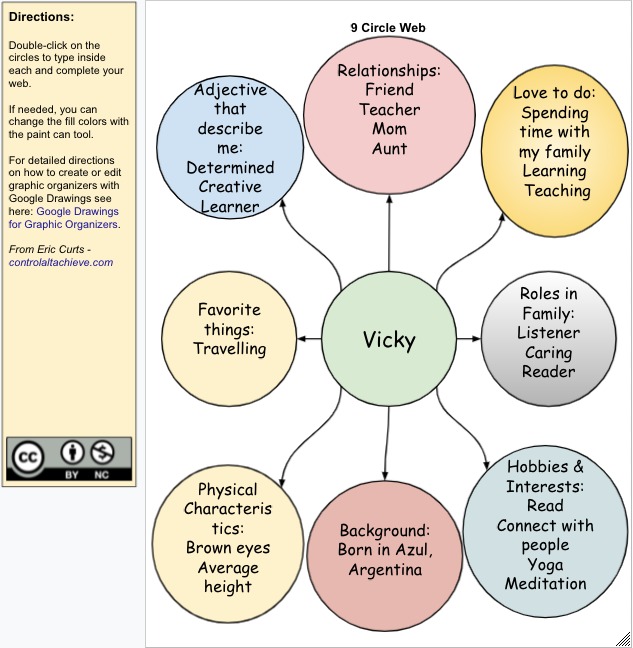

This exercise reminds students that a person is more than its physical characteristics. I include an example that shows this from an activity that I created as part of my own professional development during an ISTE conference.

The cultural iceberg becomes our framework

We might continue by asking what happens when two cultures come together and what elements of those cultures are shared at first. We connect the topic to diversity and extend it to linguistic diversity, for example. We can talk about music as a universal language, distinctive but unifying. We can also talk about literature, food, and clothing. We conclude that for the most part these are products of a culture.

After defining the words ‘products,’ ‘practices,’ and ‘perspectives,’ I proceed to ask students to sketch an iceberg and add those words to it.

We refer back to what students said about culture earlier. Students generally conclude that they concentrated on the part of the iceberg that is visible. It is what we see of a culture, mostly its ‘products.’ Just below the surface we find the ‘practices’ or how it is done. Finally, the part of the iceberg that is even deeper, refers to the ‘perspectives’ or why it is done.

Having incorporated the ‘cultural iceberg’ framework in my teaching has allowed me to help my students expand the lens through which they study a language. It has helped them to find the differences as well as the similarities among humanity. It has also helped me anchor my teaching.

What are you doing differently now than when you started teaching?

Credits:

https://accessjca.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Why-is-culture-like-an-iceberg.pdf